War in an Era of Intelligent Machines: Stirrups, Conoidal Bullets, 3D Printers, Lunar Nukes and Special Ops Forces

We just witnessed the first truly digital bank run (SVB), and it’s no exaggeration to say that we are now in the midst of the first digital war. We think we understand digital because we’ve been to so many talks on “The Digital Future” that our eyes roll when the subject comes up. And yet, the requirements and consequences of a digital world still surprise us.

Some will say we’ve had digital for a long time. It’s not new. That’s true. It’s the assemblage of technologies at a speed that’s new. Consider China’s ability to autonomously 3D-print a dam that’s on par with The Hoover Dam. Remote keystrokes can trigger an army of autonomous robotics to create massive structures incredibly quickly. Only a few days ago KENYO Precision Machine Manufacturing built a two-story building in Luhe in just 50 hours. China’s new autonomous Super-Dregder will create new islands in the Pacific in weeks. Keystrokes, code, and encryption combined with 3D printing now mean that a nation can create everything it needs in peace or wartime at speeds the West can’t match. That includes guns, ammo, bombs, rockets, aerial, land-roving and sub-sea drones, hospitals, livestock farms, bioprinted human organs, bones and prosthetics. We need to ask the question that Manuel De Landa asked in the extraordinary book he published in 1991, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines. What is the defining military technology of our time?

As De Landa points out in great detail, the answers are not obvious. He speaks at length about the importance of the metal stirrup. We take a stirrup on a horse for granted now. Stirrups had been around since the Chinese started using them in the 10th century AD. But, it was Genghis Kahn who realized, centuries later, that making stirrups out of iron and attaching them to sturdy wooden saddles gave his nomadic warriors “winged sandals.” With them, they could ride on horses with the full weight of their armor and the stability needed to ride hands-free. This left the Mongol cavalrymen (and women), free to concentrate on their archery, whether facing forward or backward. In 1206 his nomadic warriors swept through Central Asia astride this innovation, overwhelming sedentary agrarians, creating the “largest consolidated land empire in history.” The assemblage of metal stirrups, amour, stability, hands-free archery, and the new tactics these allowed for permitted an extraordinarily successful and sustained lighting strike across vast distances.

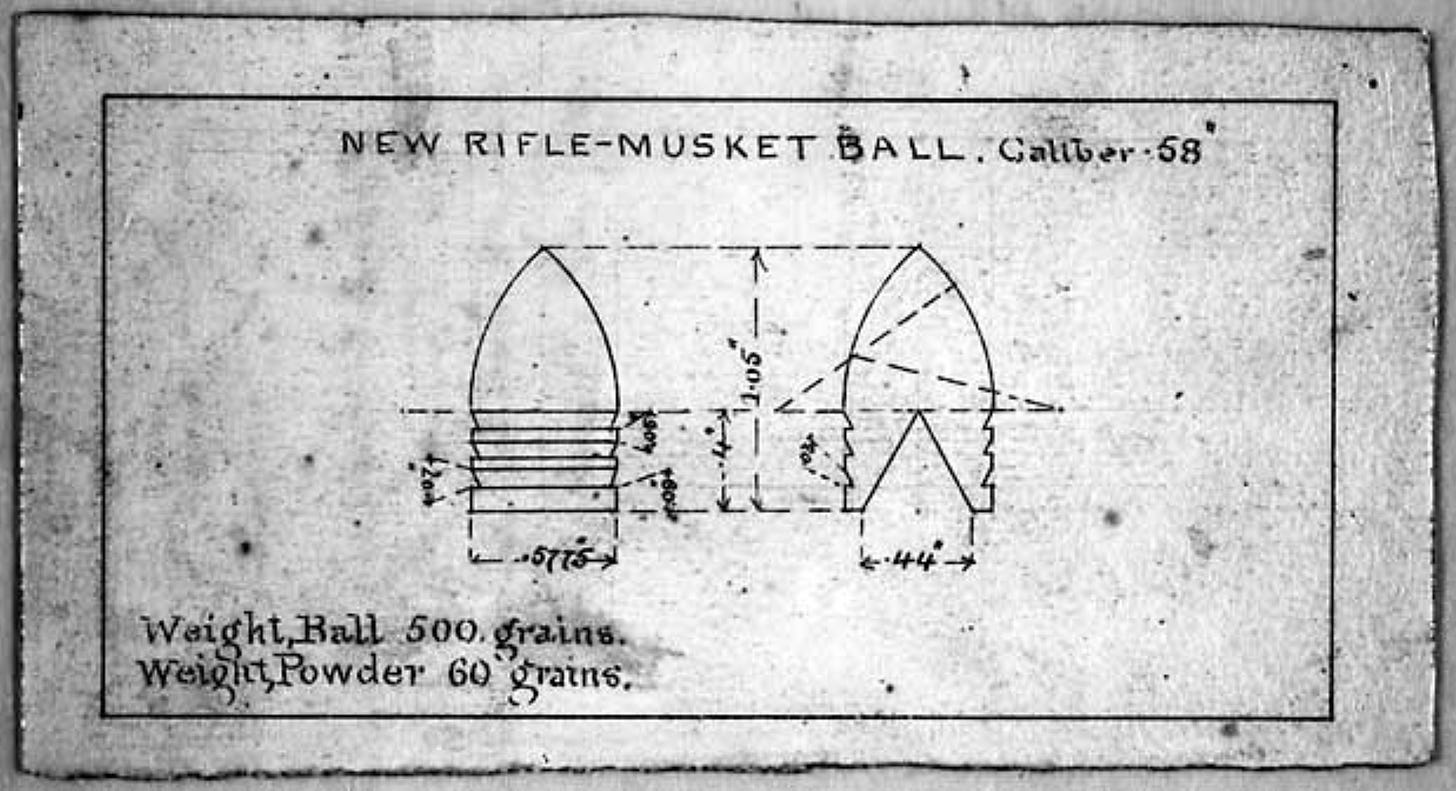

The story of the conoidal bullet is similar. The technologies underpinning this decisive innovation had been around for a long time. Humans had been developing fueling (breach loading, muzzle loading, etc.), ignition (the right weight between gunpowder, saltpeter, and charcoal as well as flintlocks, matchlocks, percussion locks, etc.), controlled explosions, propulsion methods, materials (wood, brass, lead, etc.) and shapes (Minié balls, conical, cylindrical, conoidal ), ballistics, and particular impact qualities for centuries. The assemblage of these technologies took time to coalesce into something with overwhelming lethality. It wasn’t the bullet itself that changed the course of history but the assemblage around it. The conoidal bullet required other infrastructure, like accounting systems, railways (gauges and tracks) and improved signals and communications, and quality control to shift bullet production away from being an artisanal endeavor to being a standardized, engineered, and reliably mass-produced item that an unskilled soldier could easily deploy in the field.

This last point has relevance today. In the West, everybody says we don’t need to worry about China because they have no battle experience. Is that even necessary in a digital war? It sure looks like China has returned to core principles. Sun Tzu said, “To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.” China has also already concluded that they lack the societal ethos necessary for humans to engage in warfare.

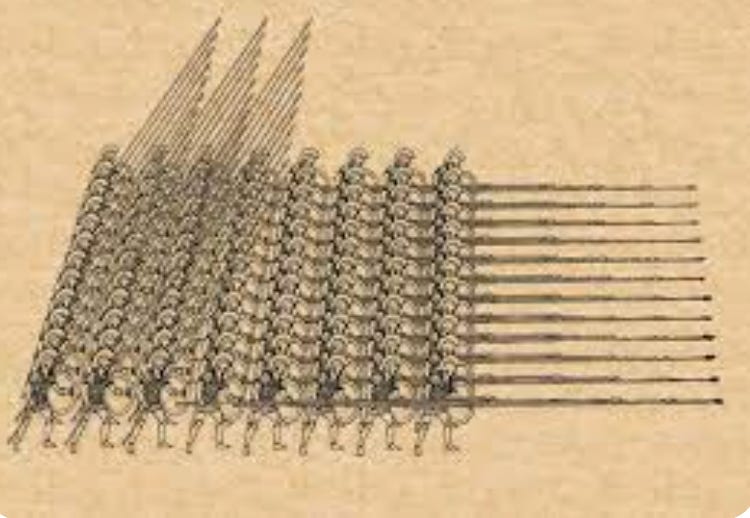

What do I mean? In college, I studied ancient Greek military history with the leading military historian of his era, Don Kagan. We went deep into The Peloponnesian War. (As an aside, everybody told me, “You’ll never get a job, and now I brief NATO Generals”). It isn’t easy to get unpaid humans to stay in a phalanx formation eight men deep and possibly very wide, especially when it’s pretty much-guaranteed everybody on the front face of the formation and to the right of it is going to die. They’d lock shields with the left arms so the right arms could be used for the long spears. The poor lefties had no chance because their right side was so exposed. A belief system is the only thing that causes that kind of coherence. We can argue about the beliefs underpinning cohesion. Did they adhere to the phalanx out of loyalty and pride? Or, did they fear the consequences of running away? One can spend hours on this. China has already concluded that humans should be kept out of the battlefield as much as possible. It’s a compelling approach. Everyone is a conscript. Even the lowly fisherman in a tiny boat technically now comes under the rubric of the Chinese Navy. But, few will be asked to fight. Instead, they are replacing humans with code. The next war for China is a digital operation run by highly responsive and obedient self-replicating robotics, informed by the best data sets and AI that exists anywhere in the world today. Humans won’t even be needed for decision-making. In conjunction with super-computing, AI is replacing Generals, especially as the warzone expands beyond a battlefield and across the entire supply chain.

What is the West doing? More weight is being placed on the most superhuman individuals in the military – Special Ops. There is a logic behind this. Special Ops Forces (SOF) have become the “easy button” because they have the military's best impact/expense ratio. They are relatively inexpensive and punch far above their weight. But as SOF leaders themselves keep pointing out, they can only do their job if supported by the rest of the massive American/NATO military infrastructure. Yet, the West is still enamored of the idea that an individual with experience and judgment will win over automation and AI.

This is the tip of a more profound philosophical split between the West and the East